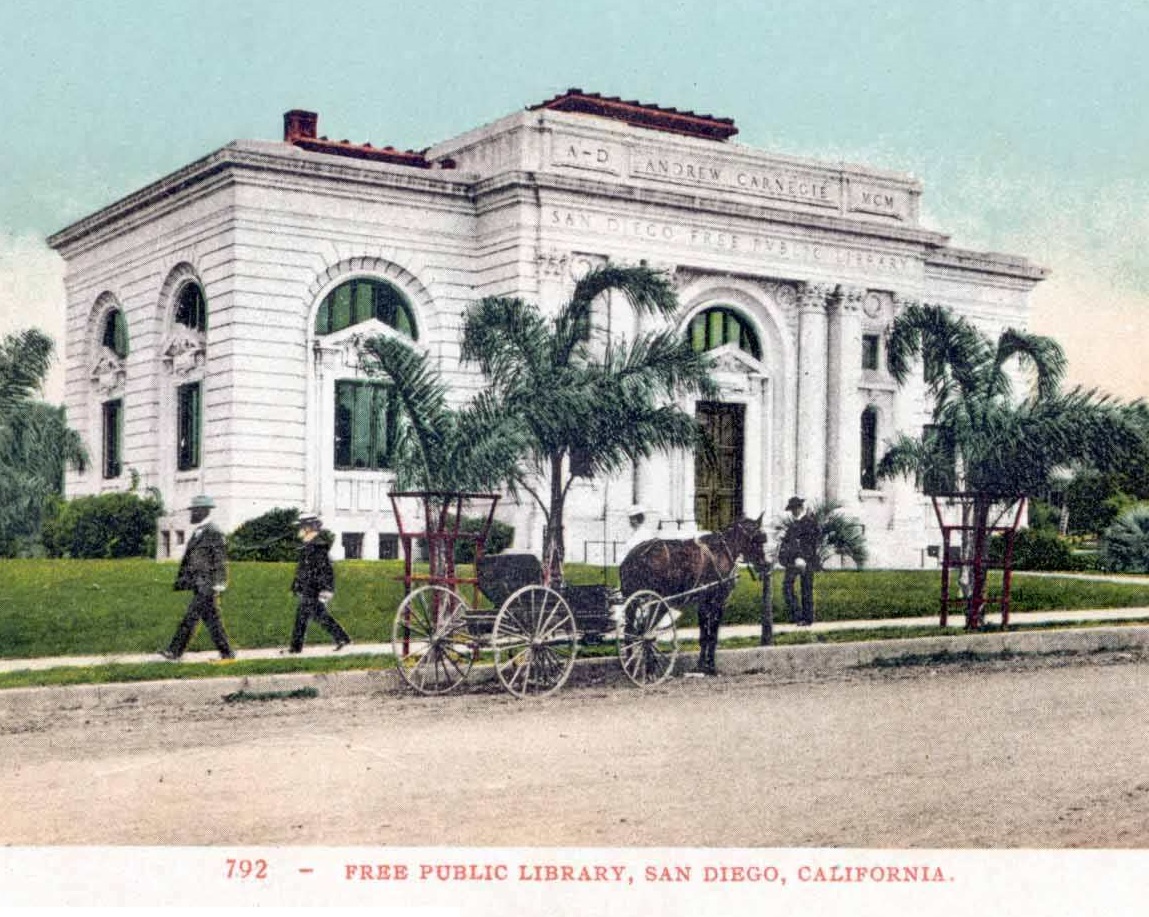

There was also an issue of community pride. The library was the first on the West Coast to have been built with a Carnegie Foundation library grant. With furnishings, the building had ultimately cost $60,000. The steel book stacks alone, cost nearly $10,000.

Fortunately, the Carnegie Foundation decided to increase its original $50,000 gift to cover the added costs, with the condition that the City of San Diego agree to support the library with at least $6,000 per year.

The new library reflected both new and old attitudes of public librarianship. Separate reading rooms for men and women were normal practice for the day.

For it to fall victim of a common burglary was a monumental civic embarrassment.

City Librarian Hannah Davison declared the value of the paintings in the neighborhood of $3,000. In 2014 dollars the loss would be close to $80,000.

Chief of Detectives Harry Vandenberg was sent to interview Butler. In his statement Butler said, “The doors and windows were locked the same as I left them Thursday night.”

Butler guessed the burglar had concealed himself in a storeroom before the library closed at 9:00 p.m. With the whole night ahead of him, the thief then leisurely removed the paintings from their stretchers, rolled them up then simply and strolled out the door.

The Los Angeles Times offered a different theory. They reported thieves “drove up to the building with a wagon, entered through a window, loaded the wagon and drove off.” How the Times came to form this opinion is a bit of a mystery.

The theft victims were Albert Valentien, Mary Williams, Charles Fries and seven others. Valentien surmised the thieves were connoisseurs who intended to sell the paintings “in the east.” But he was optimistic that the art would be found soon, “as they are so well known that it would be difficult to dispose of them.”

Chief of Police William Neely was less than confident. He told the San Diego Evening Tribune, “It’s doubtful whether any of the pictures will be recovered.”

Despite the grim prognosis, SDPD detectives used the department’s teletype system to flood cities across the United States with fliers describing each painting, title and artist.

Meanwhile, the San Diego Art Association urged the immediate hiring of a night watchman, warning that without such protection, “artists and other owners of valuable property will not be willing to make loans for purposes of exhibition.”

Two days after the burglary janitor Butler discovered an unlatched window leading to the basement in the library. The window, seemingly locked when Butler and detectives examined the building after the thefts, had been temporarily secured by someone.

Butler disclosed to a reporter from the San Diego Union, “It’s barely possible the thief used the curtain cord as a wedge by which to close the window and make it appear as though the catch had been used.”

In light of the new information, the detective bureau now theorized the thief had rigged the window frame one day and then returned at night “to throw the window wide open.”

Evidence seemed to support that theory. Suspicious marks on the window sill appeared to be scuffs from shoes. Detectives ultimately decided the thief had, “crawled through, jumped to the floor, closed the window behind him, went up into the gallery, gathered up his pictures and made his exit in the same way.”

Unfortunately, the new information didn’t place detectives any closer to an arrest or recovery of the stolen paintings.

Then, after weeks of chasing dead ends, detectives got a lucky break.

Just up the coast in Orange County, 23-year-old John Keene had been arrested for robbing a Santa Ana gun store. After a quick trial, Keene began serving a five-year sentence in San Quentin.

Shortly after his conviction, Orange County Sheriff Theo Lacey found a receipt among Keene’s effects for a package stored at the Union Warehouse Company in Los Angeles. Sheriff Lacey called L.A. Sheriff Bill Hammell and the two men paid a personal visit to the Union Warehouse. They soon located a large package of stolen goods, including fifteen oil paintings in one large roll.

They immediately recognized the art as work described in the fliers SDPD sent two months earlier.

Two months later, on April 7, 1909, artist Charles Fries took the train to Los Angeles and personally identified the paintings as belonging to him and the other artists.

San Diego Police Chief William Neely brought the paintings back to San Diego ten days later.

Art Association president Daniel Cleveland declared his organization was overjoyed. Cleveland told the press, “These pieces were of inestimable value to their owners and the association would never have recovered from the shock had they not been recovered.”

The Carnegie Library Art Heist would be the biggest crime in San Diego until thugs armed with Tommy Guns committed the 1929 Aqua Caliente courier robbery.

San Diego’s Biggest Heist

February 5, 1909 was a typical Friday morning at the Carnegie Library at 8th and E Street. Janitor Robert Butler was making his daily rounds in the glimmering three-story Greco Roman inspired building when he came across a most unpleasant surprise. As he climbed the stairs to the art gallery on the second floor, he was shocked to discover empty picture frames strewn along the baseboards. Fifteen oil paintings - part of the “midwinter exhibit” by the San Diego Art Association, the city’s first organization for local artists - had been on loan. Now they were gone.

The morning edition of the San Diego Sun exclaimed, “VALUABLE PAINTINGS STOLEN FROM LIBRARY.”

Citizens were outraged. Open twelve hours a day during the week and three hours on Sunday, hundreds of San Diegans viewed the art each day.

The CRIME FILES